Of Magnolias and Miscarriage

Perspective for my fellow women who have sat on a toilet crying

Two little vertical pink lines. If you turn them on their side, they make an equals sign. Equals what, exactly? Something, someone. Somehow barely perceptible and vividly accessible (maybe only in dreams) all at once, filling the void all women carry around with them. A void that exists for a purpose, the purpose on our shoulders at all times for many years whether we like it or not. The filling of which feels a little bit foreign, a little bit like home. Maybe a little like visiting the land of our long-lost heritage. I wouldn’t know, I haven’t had the pleasure.

The void I’ve been made keeper of has been filled six times now. Divide that by two and you get the amount of humans I’m responsible for. Six divided by two equals three. Three unaccounted for. Equals again. Equals what, exactly? In all cases, a life. A life lived or not is still a life. And I have been home to six lives.

We say “I lost the pregnancy” or “ I lost the baby”. Did we misplace it? The word “lost” would imply so. A certain sense of negligence lives in that word. Would it be so crazy though? I am, after all, prone to losing things. My glasses, my keys, my favorite lipstick-all of the usual suspects. I didn’t leave this little clump of energy made of love in my old purse, or let it slip between the couch cushions though. I found it. Between my legs, cherry red.

I had a miscarriage this week, this week in May where the magnolias began to bloom. I waffled on whether or not to share such a personal thing, but in examining my own feelings as I bled, I began to come to a conclusion that I think bears some witnessing. This experience is not unique. For known pregnancies, 10 to 20 in 100 (10 to 20 percent) end in miscarriage. It is common. It isn’t really a topic that needs “awareness” raised on its behalf. We are aware, many of us intimately so. Many of you reading have likely had this experience. What I want to illuminate in my sharing is an experience of frustration with the commercialization of our obsessions with our own fecundity (or lack thereof) paired with a very real sorrow that is based in my corporeal experience with pregnancy.

In what other context do we hear this word, miscarriage? “A miscarriage of justice”, right? A word defined as “corrupt or incompetent management, a failure.” Who is doing the managing, right now, in my body? Who comprises this corrupt jury inside of my womb? Surely they are not of me. The treasonists inside of me plead “we are simply doing as we must, this is no matter of allegiance”.

And that is just the thing. Our bodies do as they must, our bodies have their reasons. To practice surrender to these facts is really the only way to find any sort of solace. I suppose it is a very Nature is Metal kind of thing. The female body, in all matters of life-making and life-culling, is often the most metal of all. The uterus is wise, the blood it brings is purposeful, the sorrow (or relief) we feel be damned.

The sorrow right now for me is real though, and when I said that my own particular brand of sorrow is based on my corporeal experience with pregnancy, I am referring to the very specific sensations I have come to know after having been pregnant several times. I have always had a (perhaps silly) sense of pride in my ability to sense what is happening within my body. I know without fail when I ovulate. I can predict the day I start bleeding almost down to the hour. I have always known when I was pregnant before I could even make the second line turn pink. This round was no different.

When you can recognize the tiniest of sensational shifts, it becomes very easy to obsess. And I did. The signature heaviness in my belly, the particular flavor of nausea that only comes as a result of hormonal cascades, the restless, sweaty nights full of strange, vaguely creation-themed dreams. When these symptoms started to fade, so too did the lines on the tests. Happy to let go of that aforementioned pride, I reasoned my way through excuses, even though deep down I had a feeling. My urine was too diluted. The tests were cheap or faulty. Maybe I misjudged when I ovulated.

Just like I never misjudge when I ovulate and just like I always know when I am pregnant, I knew that this creation within me was a failed project.

As a creative, I have had many of those. Writing drafts that will never see the light of day, half-knit blankets stuffed away in a drawer with yarn too tangled to bother with, paintings with spots of blank canvas left. An exercise in wasted resources, perhaps. Maybe more so they are exercises in letting go, in re-routing more valuable resources, in honing priorities. My body had different priorities. With these priorities in mind, I am attempting a shift in perspective.

From “Lost: Miscarriage in Nineteenth-Century America” by Shannon Withycombe:

“In 1875, Emily FitzGerald suffered a miscarriage. That same year, Annie Van Ness lost her first pregnancy. In 1879, Mary Cheney wrote a letter to her husband with news of the failure of her latest pregnancy. Reading these statements in the twenty-first century evokes sadness, but also familiarity. We live in a world where celebrities reveal their own struggles with pregnancy loss, and physicians conduct scientific studies exposing the guilt and shame felt by families dealing with miscarriage. We are used to imagining miscarrying women as coping, damaged, failing, and sad.

And yet, the three sentences I wrote to open this chapter are patently false. That is not what happened in nineteenth-century America. Although each woman did miscarry a pregnancy, according to their own words their experiences had nothing to do with suffering, loss, or failure.

A look into the history of miscarriage, and into how women described the experience themselves, reveals that interpretations of miscarriage in terms of loss or tragedy are modern constructs, not historical meanings somehow inherent to the experience. Emily FitzGerald, Annie Van Ness, and Mary Cheney instead described their experiences in terms of comfort and relief, and they even used words like “joy.” Personal writings of women living and miscarrying in the nineteenth century expose the range and fluidity of responses in how women of that time understood what or who resided and grew within their expanding bodies.”

I am not interested in feigning joy, but comfort and maybe even a little bit of relief I can understand. I appreciate this exploration of the words we use around this topic. In a time where women didn’t rely on doctors and technology to affirm the signs their bodies were giving them (whether those signs pointed to a healthy pregnancy or not) and instead just existed through it, of course miscarriage wasn’t pathologized and catastrophized in the same way it is now. Perhaps that joy was connected to an understanding of the wisdom of the female body and the way in which it rightly expresses the will of the divine. In this way, the feminine body is an expression of providence, in the sense that it is carefully preserving resources. This fact demands our trust.

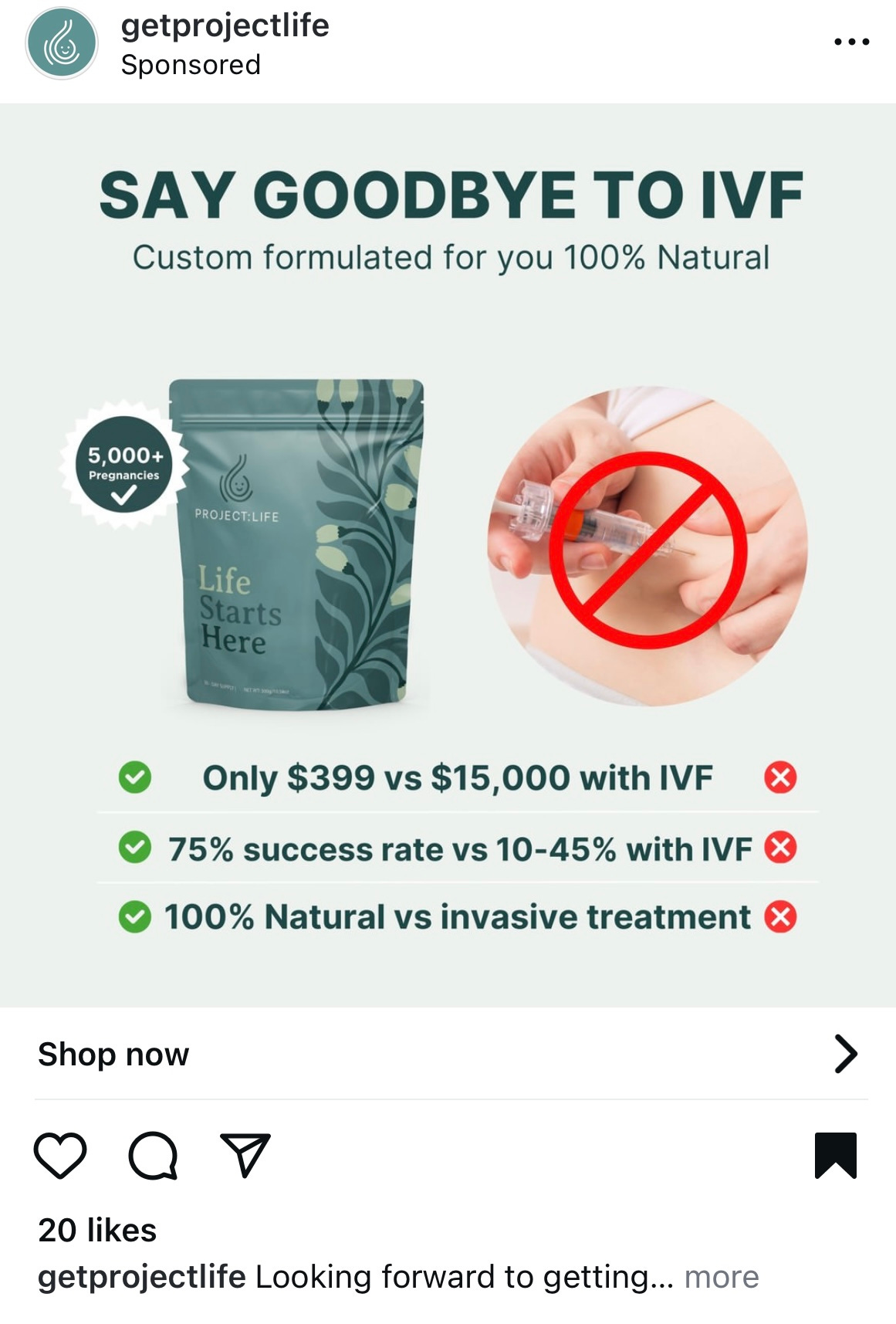

In the past few days, after searching the words “miscarriage” and “pregnancy loss” and “chemical pregnancy”, I have been inundated with ads on Instagram. Ads which seem to promise some sort of solution to the problem I wasn’t even considering that I had. Yes, I am no longer 22. Yes, I could probably cut down on caffeine. I am not disillusioned nor naive. Neither though am I overly concerned with my general health or fertility. This experience has illuminated some breaches in care of the self (not me avoiding using “self care” here) that I am guilty of, but none of those things feel particularly heavy or difficult. I have a generally hearty constitution. If anything, the fact that my body became pregnant while still tandem nursing feels like a small little win. These ads would have anyone thinking differently:

The above screenshots were the results of spending about 5 minutes on Instagram. I do not need to remove my “pregnancy blocks”. I am not interested in AI being involved in my reproductive existence. I do not want to purchase the 400 dollar magic fertility powder. I don’t want any new apps! I’m not even 35 yet! Can y’all calm down?!

This ad-related annoyance I am experiencing got me thinking about pregnancy tests, of which I have consumed many in the last few weeks. What is it about that little stick that is so enticing to so many of us? If you aren’t aware of the true pull of the pee stick, go have a gander at r/TFABLinePorn and you will quickly begin to understand. For all of my freebirthing, body-trusting rhetoric, this is an area in which I have historically gone the other direction.

I test days before it is physically possible to detect a pregnancy knowing full well they will be negative either way. I test multiple times a day. Once I get a positive, I keep testing to see the line get darker. I go full Harriet the Spy on my own uterus for a good couple of weeks until my anxiety is calmed and then go about the pregnancy pretty uneventfully. In my last pregnancy, I did all of this and then never even got an ultrasound. This leads me to ask myself- why are the physical sensations not good enough? Further, where does trust begin?

I suppose we have all grown up in a world where a pregnancy isn’t “real” until it is confirmed by a little bathroom science experiment. All of our mothers did this, many of us may have even seen the stick that confirmed our own existence in a baby book or special box stowed away alongside little leather booties and newspaper birth announcements. The pregnancy test manufacturer who produces the means by which this initial amateur-chemist-ritual-of-pregnancy is often the first of many other commercial hands which touch our pregnant bellies and babies. From the purchasing of the tests to the potential purchasing of any of the gadgets or supplements shown above, even a failed pregnancy is still lucrative for those hands.

In trying to look into the history of these tests, I came across an abstract for a chapter in Lara Friedenfeld’s book “The Myth of the Perfect Pregnancy” on Oxford Academic, which stated the following:

“In the nineteenth century, physicians developed new ways to detect pregnancy, as they sought visible and palpable pregnancy signs that allowed a physician to make a diagnosis independent of a woman’s testimony about her symptoms. In the twentieth century demand for pregnancy diagnosis increased as more women sought formal prenatal care and took on new responsibilities for self-care during pregnancy. The first pregnancy lab test was introduced in 1927 and improved over the decades, and a home pregnancy test reached the American market in 1978. Since then, the tests, which measure human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG) in maternal urine, have become a ubiquitous part of planned pregnancies, and have gotten increasingly sensitive. This means that women increasingly use them to detect very early pregnancies, many of which are not viable.”

The first sentence really caught my eye, because it speaks to my questioning of my own participation in the cult of the commercially confirmed pregnancy. I am not a man. I am not a doctor seeking some sort of dominion over the female body. I am the inhabitant of that female body. I am a woman who can give that bodily testimony. Not only this, but in cases such as that which I am experiencing now as I write these words, what comfort do those positive tests of the last few weeks bring me? Did they change the outcome? Or do they just serve to prove to myself, or to others, that I wasn’t crazy, that what I assumed I was experiencing was real? In a non-viable pregnancy, what purpose does the pregnancy test serve for us?

I’m not suggesting we all protest First Response and ClearBlue or that all women everywhere must shun this particular pregnancy ritual. I understand this is a topic that is experienced in a very different way amongst us all. I am only speaking personally when I say I am convinced it is better for myself to embrace the precarity of pregnancy without the chemical confirmation, without apps, without AI, without Reddit forums, without the internet in general. I know what is real, and I can learn how to let that be good enough, even in a world where it never is.

My 4-year-old son exclaimed “the flowers! They’re so big and beautiful!” as he escaped the confines of his car seat and bounded into the driveway of a home my husband was working on the other night. That night, I was still pregnant. That night, I sat with my little boy in an empty below-ground pool, watching him catch toads and throw cicadas into the sky to watch them fly. That night, I looked at those big, beautiful flowers and considered their name, Magnolia. I always liked flower names. That night, I hadn’t yet started bleeding.

Ultimately, it is good and precious to sit here bleeding. Not in a halfwitted “spin-every-negative-experience-into-a-positive-one” way either. Just in a life way. Would I rather not feel the excitement I got to feel for a few fragile weeks? Would I rather not have held those sweet day dreams and curious night dreams of a new little baby in my heart? Would I rather not feel the shock and disappointment I feel now? No. No, no-I do want to be immersed in it all. For this time in my life, this phase of child-bearing and child-rearing, is a time that is made for these dramas of the heart and soul and womb. I would rather feel the sorrow of lost sensations than never feel them at all. And as the sorrow passes, I can be like Annie, Emily and Mary, I can take comfort in knowing my body is taking care of herself and I can trust. I am capable of trust.

Absolutely beautiful writing. I appreciate your perspectives very much.

I gave birth to my baby boy this past January at 6 months pregnant. He did not live. I freebirthed him in my bed, in trust and euphoria, and spent those precious few moments with him while he was still attached to his placenta. I have beautiful community that supported me through it all. My dearest women surrounding me while I labored, each of us knowing the grief on the other end and all in anyway. The whole experience was a blessing that expanded me in unforeseen ways.

To be a woman is to hold both life and death. Certainly that’s what the business of making and birthing and raising those babies requires of us. In my grief I took immense comfort in allowing its colors to run with the grief of every woman who has carried and birthed and grieved a baby. To just know I was but one of many women to experience this specific type of love and mourning…

My prayer is that one by one we shift this most intrinsic feminine capacity back to one of trust, awe, and mystery. It strikes me that although I find my story overwhelmingly beautiful and full of love, there are many who would not understand why I made the choice to stay home and leave birth and death where it belongs.

Blessings to you Emily.

thank you for sharing. I think as common as miscarriage is there not a lot about processing. As someone who has had 2 miscarriages, these losses are real just as the joy was at seeing those pink lines. I always think of my miscarriages as the death of a dream, the dream I had of who those babies would be the minute I knew I was pregnant. I also have realized that there is nothing but surrender available. thinking of you🙏