Variations of Normal

Freebirth has a reckoning: the fetishization and commodification of life making and life bringing, and the monetization of female heritage

Note: Thank you all for reading, and I want to note that I wrote this while in early labor several days ago, a labor that did indeed culminate in my third unassisted birth. I am wholeheartedly in support of women giving birth in whatever way they choose, I am stringently NOT prescriptive about it, and my condemnation of an online “community” is not a condemnation of any birth choice.

I also am 8 days postpartum and likely will be slow to respond to comments, but please know I am reading them and appreciate all discourse and will respond to everyone as time and my baby allow!

When I had my 40 week appointment with my midwife, I was nervous. I am a nurse with obstetrics experience and was suffering from a case of “knowing too much for my own good” and had convinced myself I would get preeclampsia in the last week or so of pregnancy, so when the nurse applied the blood pressure cuff, I felt myself tense up. Logically, I knew I was showing no signs of preeclampsia. Illogically, my anxiety-prone thinking brain who has given IV magnesium to an endless amount of women to prevent seizures due to preeclampsia, told me “why should all of those women suffer this and not you? You’re older now, you know. It’s bound to happen”. I told my brain to shut up. That tactic didn’t work.

What worked, and what I spontaneously had started noticing myself do, was imagining my 5 year old son laughing uncontrollably the way only goofy redheaded 5 year old boys can. I saw him throwing his head back, shiny little teeth bared, eyes closed, rolling around in total hysterical bliss. This is what I thought about to calm myself down. The nurse told me my numbers are fine.

I didn’t have a midwife for my last child. I didn’t have a provider at all. I ended up giving birth1 to a healthy breech baby girl in my bathroom, with my husband assisting. There was no blood pressure anxiety. There were no box-checking questions asked as a matter of protocol. “Will you breastfeed?”, “Do you have a breast pump?”, “Which pediatrician do you plan to use?”, “Do you want a Flu shot?”.

No ultrasounds. No Dopplers. No blood draws. No appointments to schlep myself to. Just me and my baby. When fear crept into my consciousness during that pregnancy, I found it much easier to access the part of my mind which offered up the image of my happy boy laughing during my blood pressure check. That part of me was closer to the surface, less obstructed by the skepticism of others. It was truly very special.

With my pregnancy before her, I did have a midwife but I chose to not call her for the birth. That pregnancy, the one where I grew that redheaded boy, was an exercise in attunement to myself and my spirit. As my pregnancy progressed, I went from seeking care at a hospital birth center, where I quickly became dissatisfied, realizing that much of what was being (expensively) sold was just a more aesthetic version of what I had done when I worked on the Labor and Delivery unit in the past. The waiting room was beautiful and they had bathtubs and candles and walls painted calm colors, but their policies were stringent and the care was disjointed.

I switched to a home birth midwife after making these realizations and I truly relished the preparation for giving birth in my own space. I thought I had found the solution, one that balanced my need for comfort and privacy with my desire for reassurance. Desires and needs are ordered in a specific way, though, and I found the longer I progressed in my pregnancy, and the more attuned I became to what I needed, that my desires were based in the heavily ingrained belief that another person’s expertise was more valuable more than my own. Needs are the foundation that desire sits upon though.

As I considered what my needs were, I realized I was actually very anxious about the idea of having this woman, still somewhat a stranger, in my home during the most intimate and intense moments I could imagine. The desire that sat upon my need for true privacy and access to my own thoughts and intuition free of other’s opinions and fears shifted once I made this realization. My desire shifted into a desire to give birth on my own. So that is what I did.

This is where my prior fascination with The Freebirth Society becomes relevant. I cannot say exactly what it was about the podcast episodes, but I found them and I listened to them religiously. I progressed through my pregnancy, still seeing my midwife regularly and all the while, Emilee Saldaya cackled in her knowing, irreverent way in my earbuds as I did the dishes and folded the laundry.

As I listened to women tell their tales of unassisted childbirth, I was enthralled, sometimes moved to tears, and very much felt a shift within myself, a shift which told me that I was no different than they. The podcast truly did help me to remember some fundamental truths about what birth is, what potential it holds for women, and how it has been largely manipulated and desecrated by many of the policies and procedures of modern obstetrics and the “fathers” of this branch of medicine which came before the modern version. I am grateful for the illuminative experience this granted me.

The thing is, though, that those illuminations and realizations are not the result of “the movement”, or Saldaya herself—they are the result of female storytelling. I do think birth stories matter a great deal.

With my first child, whom I did have in the hospital, I read the entirety of Ina May Gaskin’s Guide to Childbirth the night before I went into labor. It was the words from birth stories of other women in that book that I repeated to myself in my mind and heart as I birthed my daughter into the world less than an hour after arriving at the hospital. The words of other women, women I will never meet, were what helped me stand my ground where it needed standing, and were what told me “no, you aren’t going to die” when I thought that that was a real possibility during transition.

It is a mythic thing, the quality that these stories of life making and life giving take on. Like war stories or tales of great exploration, birth stories function to transmit to us our own potential, while also serving as warnings and teaching lessons. At least, when properly told they are.

In Hannah’s Children, economist Catherine Pakaluk states the following about her qualitative research method of collecting stories, used in examining the reasons behind why some women choose to have bigger families:

The story is the ‘observation’. The stories are basically narratives. The question is thus what to do with the stories. Typically, stories are not analyzed as statistical data; stories are 'interpreted.... The stories [act] not as data points but to suggest particular revisions in theory.’ It is in this spirit that I took up this work: to find the stories that may ultimately assist in a revision of economic theories about birth rates and population growth.

I share this because I think the concept of using stories as a tool for revision of theory is important. I do believe that in sharing stories of birth, women offer something really potent to one another—the potential for revision of one’s own personal theories on birth. This is often very necessary in a culture where birth is framed as somewhat of a necessary evil, a punishment for original sin, the thing on TV where women scream bloody murder and husbands pass out, or even just the annoying, sort of gross thing you must do in order to earn your prize, the baby. Birth is something to fear, laugh at, groan at the idea of, and ultimately just accept and deal with in our culture. A far cry from a birth rite, a gift, a shift from one version of ourselves to the next necessary version. Some revision is needed here. Not because everyone needs a magical, transformative experience, but because the experience really is more than all of those things.

The issue that arises with Saldaya and her brand is that the stories of women are not just told for the benefit of all women, but more specifically for the benefit of the founders of the “society”. The podcast is the catalyst for sales, plain and simple. While I stated above that there are some real benefits to being exposed to the stories of women who have given birth unassisted, I think that there is a lack of balance due to the need to stick to the narrative. The true lessons and the warnings that exist within women’s words are brushed aside in favor of sarcastic admonishments of anything that doesn’t serve that narrative. Revision becomes impossible when there is a specific narrative to sell.

What is the narrative exactly?

The narrative that Freebirth Society adheres to is one where every situation in pregnancy and birth that is associated with increased morbidity and mortality is simply a “variation of normal”, where grappling with death is the task of the woman who accepts their version of “radical responsibility”, and where every single medical provider is a brainwashed, paid lemming of the industrial medical system.

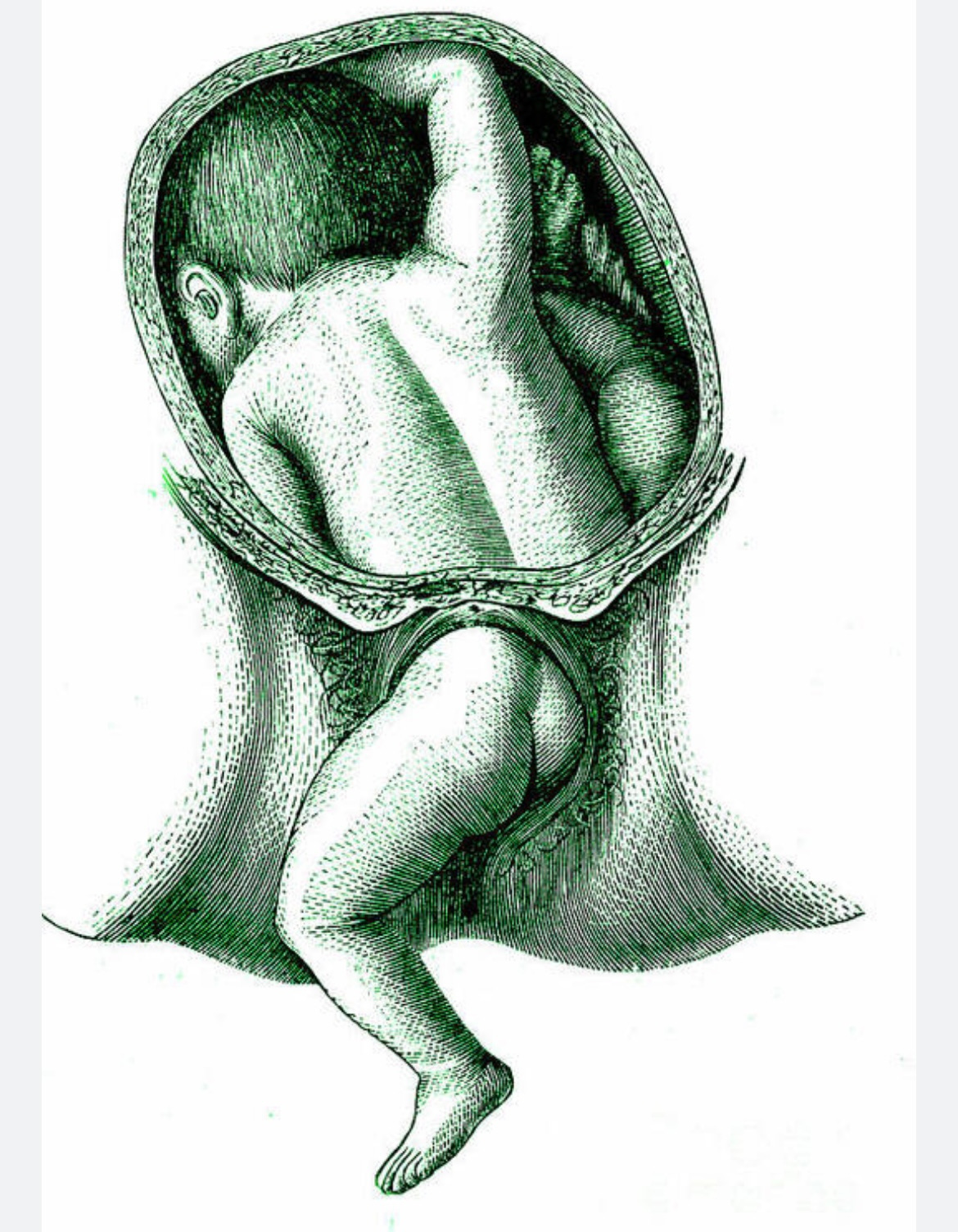

19th century illustration showing a foetus in a left sacro anterior position. Published in 1864.

I want to be clear here. I do think certain complications and situations of the childbearing continuum are absolutely over-pathologized, over-managed and over-catastrophized. I do think that this is a result of the inherent CYA culture of medicine, where litigation is so prevalent and where providers do not want to sully their reputations. I also think medical providers are human beings that do not want to be involved in tragedy, not because of their egos but because they have souls. Additionally, I think the language of “variation of normal” negates the definition of normal, something meant to describe the standard. If everything is a variation of that standard, then there is no actual standard, and standards do matter. The podcast Saldaya profits from benefits from stories which suggest the opposite.

I was actually a guest on the FBS podcast, and I was actually interviewed twice, with Emilee losing my first interview.

I myself parroted the words “variation of normal” over and over when discussing my breech baby. I found myself repeating the words I had heard so many times without really considering what they meant or what I meant. Now I can examine my experience and my knowledge and understand that breech is not normal positioning for a baby. It also isn’t inherently bad or a reason to panic, and it certainly isn’t a real reason for an automatic, default C-section. “Not normal” doesn’t necessarily mean “not acceptable”, but it does in fact mean not the standard, and the standard is the safest.

I am grateful for my vaginal breech birth. I am grateful I built up the courage to not fear it. I acknowledge that some of that process was started by my personal exposure to the FBS podcast and the stories of the women shared on it. I also am grateful to have experienced a pregnancy with no prodding, no prepping, no fussing. Life was just life for that pregnancy, and birth is a part of life. That is the true normal-but my baby’s positioning was not.

Her positioning actually caused me a lot of physical pain towards the end of my pregnancy and potentially could have caused her harm, but it did not. I can both acknowledge my own courage and faith and be grateful for my experience and also acknowledge that there was some luck and risk involved. I also think having a malpositioned baby demands the question of why? I think it is worth understanding what is going on with my anatomy or my posture, my biodynamics in general, that may have caused this positioning.

When the narrative of “variations of normal” is pushed, the true answers of why those variations are present are not available for finding, because one is not looking. For all their talk of radicalism, there sure is a lot of ignorance and denial of root cause.

As for radical responsibility, I also will say that parents do need to take full responsibility for their choices, their babies, and themselves. The reliance on experts to tell us what to do is a common tendency of many people that often takes us away from our own knowledge and understanding. With this, it is not that no woman should ever seek the guidance of someone who knows more than she, it’s that women should not blindly trust the expertise of others without also fully trusting themselves. I don’t think there can be true responsibility without true trust in one’s own judgement. The other side of this coin is the idea that in order to be truly “radically responsible”, we have to accept every possible outcome in birth without question, revision, or exploration of the why as described above. This can be in conflict with our responsibility to protect our children, though.

Which is the higher responsibility for the mother? The responsibility to protect and cherish the lives of our babies? Or the responsibility to adhere to the ideal of not seeking assistance?

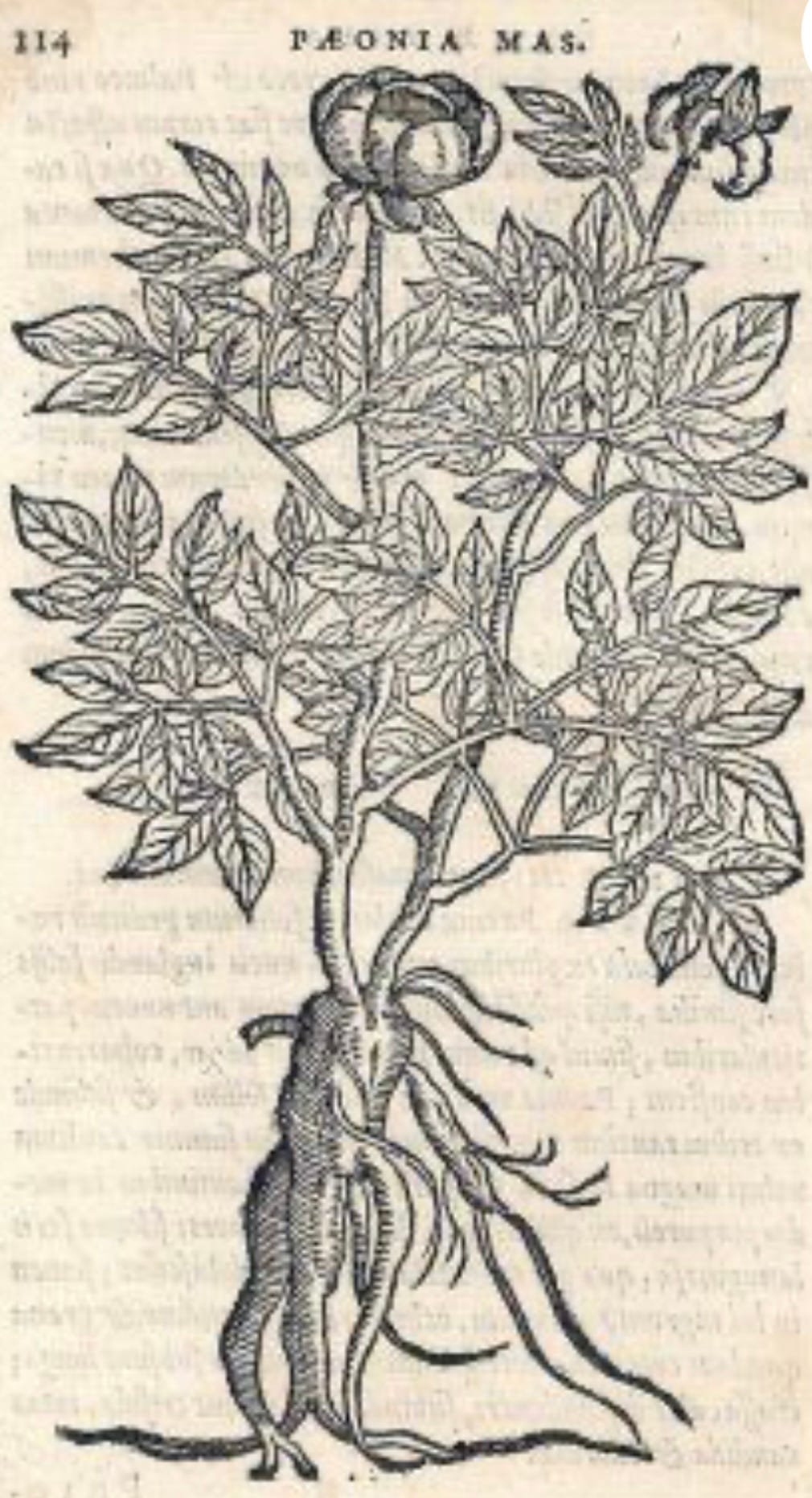

The rhetoric is clearly very dogmatic and in some ways very far from the true meaning of radical. If radical means “from the root” or “of the root”, I suppose we must consider roots. The things which dig down deep into the unknown Earth, smelling wet and fertile, grabbing and pushing and gobbling up nutrients for the plants above. Roots are searching and surefooted. They are often very strong. Their purpose is both nourishment and stability. These qualities are protective of the plant, just as mothers must be protective of their babies. Between all of these qualities, we can see that a word sprung from their existence must be a very significant one. Does radical mean to be extreme as most people understand it to? Or does it actually mean to be steady and reliable and protective, a metaphor that draws a parallel between sturdy plant anatomy and sturdy human qualities?

16th Century Botanical Woodcut - Peony - by Dodoens

With this understanding of “radical”, I think that the Freebirth Society version of it-where it takes on extremes in matters of life and death where the protection of life should be tantamount-is just a way to defend the flaws in their ideology.

When Saldaya interviewed me for the show, she was particularly interested in my experience as a labor and delivery nurse. While telling my birth stories as instructed by her to, I felt she was rushing me through the birth part to get to what she actually wanted me to speak on. She was noticeably annoyed that I was not giving as many details as to the problematic aspects of that work, and snickered at some of my comments, even correcting me at one point about why obstetricians are not trained in vaginal breech birth, interjecting her own narrative as usual. Perhaps my comments about the medical industry weren’t enough to be as thrilling of an exposé as she hoped for. I have written about the problematic aspects she wanted me to tell all on at length in the past. I believe these problems are real, and they are indeed rampant.

I also do not believe that all medical providers, myself included, are those brainwashed rodents she tends to characterize us as that I mentioned earlier. In my career I have met providers who I could apply those descriptions to, but many more of them are those who I would never apply those words to. I know I certainly wouldn’t apply them to myself.

Currently Emilee Saldaya and her co-founder Yolande Norris-Clark (

) are getting majorly dragged all over the internet. It’s very popular to hate them now, and for this reason I really questioned my motivations for writing this. The truth is, I have had a version of this essay in my drafts for over a year. Sometimes we need a push to find the courage to say some things that need to be said, and reading the words of other women who have been honest about their experiences led me to that courage. I’m not motivated by hate or the desire for sensationalism, I’m motivated by the desire to lend some brevity and steady footing to the discussion. There must exist some poise in the debate of what it is that will best serve women and babies in birth and the early years of mothering (not to say others have not lended this same angle to the discussion, of course).Some typical FBS rhetoric…

This isn’t the first time they have been in the spotlight, as evidenced by this older Rolling Stone article, as well as this one from NBC. The current fallout is specifically coming from inside the house though—the women who have been involved in their programs, who have paid them to be a part of their vetted online community, and even women who have lived on the property Saldaya bought in North Carolina—not skeptical and sensational big media outlets. There are assertions that the group is a cult, as seen on

’s podcast2 (The group isn’t specifically named but it is clear to anyone who has followed FBS that they are the group being alluded to. The cult dialogue seems to perhaps have been spurred by ’s podcast episode3 on cults and German New Medicine. I just happen to regularly listen to both of these productions and also have followed along with the Freebirth Society Lore over the years so I was able to understand what was being said without the hosts fully saying it.After those podcast episodes dropped, a quite revealing subreddit about the founders and their communities and programs and festival popped up and was widely shared over on Instagram. I cannot help but peek at it occasionally to see what the topic of the day is. I was not surprised by what I saw, and what I saw is not good. Getting into the specifics of it all isn’t something I have the capacity for but

may be a good place to start if interested.This is all probably somewhat niche and in my discussion of it all I am certainly exposing where I have spent too much time on the internet, and yet I find the entire discourse around it to be worth examining. Gossip aside, there are a few issues this all brings up that touch the business of women. After all, birth-giving and birth-tending are the most obvious women’s work.

The core issue with FBS is that it is actively shape shifting the stories of a multitude of women paired with some knowledge of physiological birth—information that should not be shrouded behind a veil of an internet paywall, overpriced to fill the pockets of women who cry expert-worship left and right but who, in charging for their knowledge of basic childbearing information, have in fact positioned themselves as experts themselves. The knowledge they sell is knowledge that isn’t a possession of few, it is the heritage of all women.

Gathering information takes resources and I don’t think that women who share these things, whether it be FBS or any other woman, should be expected to put their resources into something and not be compensated. The issue isn’t compensation—it is the hypocrisy in their messages of anti-experts and anti-midwives (while positioning themselves as experts and creating their own “midwifery” school) paired with astronomical prices—a combination of factors that betrays their greed and egos.

Sharing women’s knowledge is something that must have integrity attached to it, and if this is lost, that heritage is poisoned. I would rather learn from a grandmother in my community or family about birth and mothering any day, than from internet grifters who overcharge for “community” and basic information. Women, myself included, idolized this group because their message was something we were not getting in our real life experiences. That does not mean those experiences are not available to us however, it means we must actively search them out. We should be asking questions, seeking stories, and keeping communion between ourselves as women. In real life.

We should share our own knowledge and experiences with the young women in our lives so that we may replace those who selfishly build their livelihoods on our unfortunate dearth of women’s knowledge.

When I say “women’s knowledge”, I realize it may sound like a vague, silly, woo-filled, empty phrase. I think it is because language like this has been used so widely by businesses and “coaches” on the internet for years now that many of us hear and immediately roll our eyes. Women’s knowledge and heritage is a real thing, though, it isn’t silly or precious or just a shiny thing we have to pay for in order to feel special. Basic information passed down from woman to woman about our physiological realities, capacities and capabilities is the language by which humanity is built and nations are born.

In a recent article about FBS in Marie Claire, author

aptly stated the following:“By the time I got pregnant, in 2020, the “birth story” had become an inescapable element of human reproduction. Childbirth was not just a natural process, or a medical event, but an experience—a climactic moment in the narrative of the pregnant person’s life. A birth could be choreographed, stage-managed or even filmed in real-time and posted to social media. And if a typical birth represented a good story, a freebirth was positively mythic. It was woman vs. nature, woman vs. society, woman vs. herself. Freebirth aligned with the imperatives of social media platforms to push content to its furthest extremes. It could be styled as a feat of physical and mental but also commercial control. If the birth went viral, it could even launch a personal brand.”…

“The Freebirth Society’s birth stories were just the free tier of a vast digital marketing project. I signed up for the society’s email list and my inbox filled with pitches for its many programs, which it called containers and offerings…”

This excerpt perfectly captures the antithesis of the sort of sharing of stories I am suggesting above. The sharing of other women’s stories as a marketing ploy is quite exploitative. In extracting the compelling, the beautiful and the often shocking nature of a multitude of women’s personal experiences for personal financial gain via all of these programs/trainings/vetted communities/festivals that were tied to the podcast and the brand, the brand itself was utilizing these women as walking, talking advertisements for their rhetoric, and with the rhetoric came the consumable content with a hefty price tag attached to it.

Stories should not be catalysts for business and profit or career building and influencing power. They are catalysts for revision and potentiality, for hope and faith, and for understanding.

In many ways, Saldaya and Norris-Clarke have taken what is a personal choice that every woman has a right to and turned it into something very rigid and fetishized. When something is elevated to fetish-level devotion, the door to monetization flings itself wide open. They monetize birth, female friendship and community, herbalism, “conscious conception”, radical feminism…the list that goes on and on. There is nothing radically responsible about capitalizing on every aspect of what it is one deems “wild”.

I recently chose to make my Instagram page private due to a strange influx of strange men following along and “liking” one particular photo of myself, my pregnant belly prominent but very much appropriately covered. I began getting follows from accounts called things like “iheartpreggos” and getting DMs from men asking when I was due and if I planned to breastfeed. I spent a few days blocking people and eventually got fed up and digested enough to make it private, which was a good choice and one I will stick to. This experience reminded me of how the image of the pregnant woman is a highly fetishized one.

The photo in question. I feel like Substack is a safer place for it, don’t prove me wrong! Dress from .

How did we come to settle in a place in time and history where the physical manifestation of vitality is so perverted? Considering art history, from crude fertility figures with large hips and breasts to images of the nursing Mother Mary on church walls, we can see that the maternal image has long been admired. The image of the pregnant or lactating woman is one that holds power. What used to be a place of honor and purity, or at least of fascination and mystery, is often now replaced with fetish pornography or images used to sell things to pregnant women themselves. The difference is where the power lies. It has largely shifted from the maternal body to the observer of the maternal body.

In the same way these random men were fetishizing my pregnant belly, programs which sell extreme rhetoric to pregnant women are fetishizing birth. These entities have something very important in common-they are commodifying the act of life creation. They are different strains of the same disease, the disease of vitality fetishism. The irony is that in the fetishization of the image and practice of pregnancy and birth, these sacred things become representative of a sick culture. Only in a sick culture can pregnant women be perceived solely as sex objects for masturbation fodder. Similarly, only in a sick culture can unadulterated childbirth be seen as an internet-based business opportunity for pseudo-mentors who praise matriarchy while simultaneously charging regular women hundreds and thousands of dollars just so they can acquire the illusion of friendship with them via digital proximity.

I suppose this begs the age old question of can one separate the art from the artist? Can I acknowledge that Saldaya and Norris-Clarke played a part in my reckoning with my true capabilities and in opening my heart to greater possibilities when it came to birth while also recognizing that their business model is one that is contributing to the ongoing commodification of maternity, much in the same way they would say obstetrics is? Yes. I appreciate the stories they brought to my ears. I more so appreciate the women who were interviewed. I am grateful to have found just how significant the sharing of female experience is, and am very committed to doing so in my own life-both as the listener and as the storyteller.

What I am most committed to is the work of transforming the maternal body from a fetishized object into the much-needed anti-machine. The maternal body as anti-machine will only become more and more relevant as we move forward in this environment so hellbent on widespread assisted reproductive technology and which so encourages things that shut us off from our embodied selves such as birth control and pornography. Everything that seeks to profit from both procreation and the avoidance of it, and including that which inspires it-sexuality-is a facet of the extractive machine which sees life as valuable not just for the fact that it is life, but because it drives sales and controls people.

The maternal body is woven together with the maternal soul. Not only this, but also the fetal soul and body as well. All deserve true protection and stability, all deserve love and honor. The maternal soul deserves real, not bought and paid for, friendship. No sales, no memberships, no extremes. The Freebirth Society was compelling to myself and countless other women because we were looking for something that has largely been lost, and that something is the sharing and storytelling of the heritage of birth. Thankfully, we can absolutely have and benefit from that storytelling without the ego, without the dogma, without the rigid narrative, without the fetishistic inclinations, without the condescension and sarcasm, without the commodification, and without money changing hands.

Women deserve other women, and babies deserve mothers who are supported by other women who love them, not “coached” or “mentored” by women who charge them for basic information and the illusion of sisterhood.

Undomesticated Birth

Birth is like an all-knowing, all-consuming character to me- wisdom and beauty and fury and divine purpose manifested into this beast of an experience. Because birth is an experience-it happens to you. The woman is a vehicle for the sensation necessary to propel another human into this life. Birth happens whether or not the woman consents, contractions …

I have been volunteering with ICAN, since they are the only organization that helped me with my VBAC that wasn't trying to sell me something. And of course they are not sophisticated compared to all those sick little OB influencers or FBS, and much diminished in power post COVID (picketing hospitals that ban vaginal birth seems like a beautiful dream now), but we get on zoom and we talk about our bodies and there's nothing like it. Nothing. I wish more women knew about ICAN.

You mention learning from a grandma. The grandmas I know had twilight sleep and their breasts forcibly dried up. My mom and my female relatives had episiotomies and cesareans. There are no female elders on either side of my family with birth wisdom to share. None. I've had to piece things together while squatting in what felt like a pile of ruins.

I have a daughter and believe I may have another one day. I want to do doula training for them, so that someday I will have something intelligible to say to them, or their friends. If I can do nothing else in this world, I can do that.

Thank you for writing such a thoughtful and personal piece, Emily. The story aspect has been a major part of my reflections on all that is happening in the freebirth world. It's always bothered me that the women who shared their birth stories with Emilee were not compensated for what they gave her, nor were they truly respected by her. I'm sorry to hear that she disrespected you as well during your interview. You deserved better than that. Far better.

I worked for Emilee S. as the Free Birth Society social media manager in 2023. This was before the "midwifery" school was started but right around the time everything began to take a turn for the worse. All but one woman that I worked alongside at that time has since left the brand. I remember Emilee complaining during a team Zoom meeting about how "boring" all of the birth stories were, and how tired she was of doing the podcast. She continued on, saying that she had to keep doing it because it's obviously what draws people in to the FBS brand, but she was not pleased about it.

There are many more examples I have of how little she values the women in her community and the disgusting terminology she uses to describe them. I'm working on writing a piece about it but have had to pause multiple times to recenter myself and make sure I'm staying aligned with my own storytelling values. The piece I recently published about FBS speaks to the storytelling process in these circumstances where trauma and vulnerability are involved. There are many women staying silent about their experiences with Emilee and Yolande because it's scary to make yourself vulnerable, especially if you worked for the women being discussed and have seen the way they behave when their audience isn't watching.

My personal writing experience has been a lot of back and forth about whether or not I'd spend the time diving into the topic. I was embarrassed about working for the brand and my ego did NOT want anyone to know about my proximity to FBS. I eventually felt that I had a personal responsibility to share what I know because a lot of my marketing copy resulted in people registering for the RBK school and attending the Matriarch Rising Festival. In order to undo that, I feel that I must write the truth about FBS. This doesn't mean I think everyone involved has the same obligation, but I know this to be what's required for my own journey through this unraveling.

Like you, I've written a variety of pieces over the years about my thoughts on the commodification of birth and motherhood, as well as the questionable practices of Emilee and Yolande. I never felt ready to publish them publicly because I didn't want to experience any more negativity than I already had while connected to FBS. The more inspiring pieces to write have been those that concern themselves with the solutions I've come up with regarding accessible and thorough childbirth education and our responsibility as mothers to be the ones to teach our children about birth. I'm still inspired by these pieces and look forward to making use of them in the coming months. This particular piece you wrote and published today has made me feel even more confident in my choice to write about the FBS situation and what the future holds for those of us who choose to write about birth and motherhood. I thank you very much for this.

At the root of this reckoning is the simple truth that women's wisdom and knowledge were stolen from them a long time ago (twilight birth is a great example of just how far women were misled), and it's a complete shame that women are now selling that stolen, sacred wisdom back to one another for ridiculous amounts of money. The internet isn't meant to be a pawn shop for stolen wisdom! Luckily for all of us, we have the power to reclaim this narrative by telling our stories fearlessly and on our own terms, whether they are about birth or the regrets we have regarding where we've spent our time on the internet ;). Stories really are so very powerful. Thank you again for sharing yours (and congratulations on your new baby!).

With love,

Kaitlin